Armies in the 17th and 18th century CE were significantly larger than in the 16th.

The Prussian army was even larger, at least relative to the size of the state that supported it.

By the end of the reign of Frederick William I's reign, there were 80,000 soldiers on a population of 2.5 million, using up 75% of the state budget,

in a time when that figure was 20%- 30% for most states.

At the start of the Seven Year's War, with Silesia already added to the kingdom,

the army numbered 150,000 and by the time of Frederick II's death 200,000, less than half of them native Prussians.

It was said that in Prussia, the army did not support the state, but the state the army.

However it took time and money to train and equip these large forces and states were loathe to waste them in battle.

The aim changed from beating an enemy in battle by force, to outmaneuver him, cut him off from supplies and forcing him to retreat.

The importance of terrain and strategic points was recognized; mathematics and topography became part of military strategy and tactics.

40% of the Prussian army were 'volunteers', men seeking a career in the military above alternatives.

Some were foreigners, but most native Prussians.

The other 60% of the army was recruited through a kind of indirect conscription in a regimental system.

The country was divided into districts, each supporting a regiment; these into cantons, each supplying a company.

All citizens owed military service to the state, but they were to some degree free to choose among themselves who would serve, as long as the required numbers were met.

In practice it was mainly peasants and unskilled workers who ended up in the ranks.

Many did not relish the hard military life and high risk of death; desertion was an ever-present problem.

In response the Prussian leaders enforced a notoriously harsh discipline.

Transgressions were punished by running the gauntlet, or in severe cases, hanging.

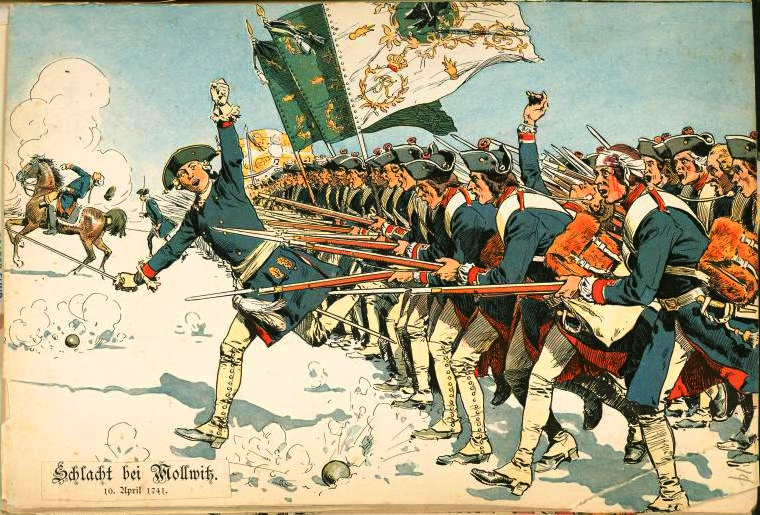

In some ways soldiers were taken well care of, receiving splendid 'Prussian blue' uniforms, good medical care and suitable retirement options.

But in return they had to submit to the strict discipline and a high death rate in many years of fighting.

The army culture imprinted itself on the men.

There are stories of old retired veterans who hobbled after the army when it marched to battle, because life in the army was all that they knew.

The nobility too, while reluctant at first, was coerced into accepting a military career as army officer as a natural profession.

The army consisted of about and 70% infantry, 25% cavalry and 5% artillerymen.

The bulk of the infantry was made up of musketeer regiments, supplemented by fusiliers with shorter muskets and grenadiers.

There were also a handful of guard and jaeger regiments.

A standard fusilier regiment included two battalions and a small staff.

It numbered 1430 soldiers, 160 NCO's and 50 officers, totaling 1680 men.

Normally they were deployed in three ranks.

Cavalry was mainly made up of heavy cuirassiers and medium dragoons, with a smaller number of light hussars.

The artillery consisted of 80% foot artillery and 20% horse artillery.

Their equipment ranged from light 3-pounder field guns to heavy 24-pounder siege cannons.

The Prussian army was innovative in arms and tactics.

William Frederick I introduced the goose-step, marching on music, loading muskets with iron ramrods and endless drill.

In 1743 CE Frederick II added annual field exercises, to train the army, test tactics and impress both friend and foe.

All this enabled the Prussians to march quicker and fire 5 times per minute, much faster than their adversaries.

Frederick II also created horse artillery, which gave the army fast-moving field guns.

The mobility and firepower of the Prussians often allowed them to fight in what Frederick called an 'oblique order', reminiscent of the ancient Theban tactics of Epaminondas.

In it, one wing was strengthened at the expense of the other and to break through the enemy's ranks before the weaker wing could get into trouble.

War Matrix - Prussian army

Age of Reason 1620 CE - 1750 CE, Armies and troops